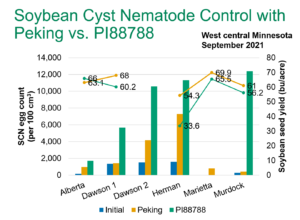

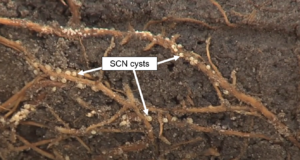

Soybean Cyst Nematode (SCN) Egg Numbers Continue to Increase

This article originally appeared in the AGVISE Laboratories Spring 2024 Newsletter.

Over the winter months, we received a lot of questions about the increasing soybean cyst nematode (SCN) egg count trends across the region. Soybean cyst nematode is the most damaging soybean pest in the United States, and the problem is becoming worse. The AGVISE SCN summary over the past five years (2019-2013) shows that SCN egg counts are increasing steadily in Minnesota and North Dakota,

which is a serious concern for SCN management into the future.

| State | Year | SCN Egg Count (eggs per 100 cm3 soil, % of soil samples) | ||||

| 0 | 1 – 200 | 201 – 2,000 | 2,001 – 10,000 | >10,000 | ||

| Minnesota | 2019 | 17% | 16% | 36% | 27% | 3% |

| 2020 | 15% | 10% | 28% | 38% | 8% | |

| 2021 | 10% | 9% | 27% | 40% | 14% | |

| 2022 | 11% | 8% | 27% | 40% | 15% | |

| 2023 | 8% | 7% | 21% | 45% | 20% | |

| North Dakota | 2019 | 43% | 15% | 25% | 14% | 4% |

| 2020 | 42% | 14% | 25% | 17% | 2% | |

| 2021 | 30% | 15% | 23% | 23% | 9% | |

| 2022 | 29% | 15% | 25% | 24% | 8% | |

| 2023 | 20% | 12% | 21% | 36% | 12% | |

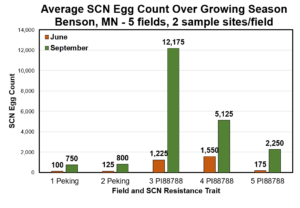

In Minnesota, 65% of SCN soil samples in 2023 had more than 2,000 eggs per 100 cm3 soil. This is the threshold where an SCN-resistant soybean variety is suggested, yet some soybean yield loss is still expected. The percentage of soil samples with zero or low egg counts (<200 eggs) has declined from 17% in 2019 to 8% in 2023, meaning that there are fewer SCN-free fields in the state. More alarming,

the percentage of soil samples with more than 10,000 eggs has skyrocketed from 3% in 2019 to 20% in 2023. This is the threshold above which planting soybean is not suggested, whether resistant or tolerant to SCN, and a non-host rotation crop is suggested.

In North Dakota, 48% of SCN soil samples in 2023 had more than 2,000 eggs per 100 cm3 soil. The percentage of soil samples with zero or low egg counts (<200 eggs) has declined from 43% in 2019 to 20% in 2023. More alarming, the percentage of soil samples with more than 10,000 eggs has quickly increased from 4% in 2019 to 12% in 2023.

These SCN summary trends highlight a growing concern for soybean growers. With SCN, an ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure. A consistent SCN soil sampling program remains one of the best tools to monitor SCN populations. This is how we learn if current SCN management strategies like crop rotation and SCN-resistant varieties are working, or if you need to reevaluate your soybean

management plan. A detailed guide to collecting SCN soil samples can be found at the SCN Coalition website.