Understanding high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen following drought

Soil testing after small grains is well underway, and we are seeing higher than normal soil nitrate-nitrogen levels, as expected. Crop yields have varied from much below average to surprisingly decent in some locations. It is easy to understand why residual soil nitrate-nitrogen is high in fields where the 2021 drought was severe and crop yield was very low. It is a little harder to understand how some fields, that produced decent crop yields, can also have higher than normal soil nitrate-nitrogen as well. Given the variability we are seeing across the region, the only way to know whether or not your fields have higher-than-expected residual soil nitrate-nitrogen or not is to sample and test these fields.

We will attempt to answer some of the questions about “Where did all the soil nitrate-nitrogen come from?” and “What should we do next year?” farther down.

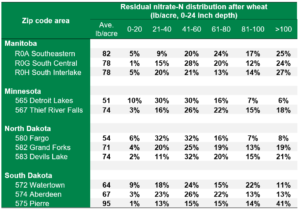

2021 Residual Soil Nitrate-Nitrogen Summary, Early Report (First 6,500 Fields)

AGVISE has tested over 6,500 soil samples from wheat fields across the region so far. We usually wait to share the early soil nitrate-nitrogen summary until September, but we have been getting a lot of questions already. The table shows the average soil nitrate-nitrogen (0-24 inch soil profile) and the percentage of soil samples in each category for several areas of Manitoba, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota. As you can see, there is considerably more residual soil nitrate-nitrogen than the long-term average of 30 to 45 lb/acre nitrate-N in a good year. In some areas, over 30 to 50% of soil samples have more than 80 lb/acre nitrate-N (0-24 inch) remaining after wheat.

Reasons for high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen in a drought with low crop yield

- Lower crop nitrogen uptake and use (low crop yield)

- No soil nitrogen loss from leaching or denitrification

- Warmer than average soil temperatures in the early growing season when soil water supply was better, resulting in above nitrogen mineralization from soil organic matter (can be 40 to 100 lb/acre N)

- Nitrogen fertilizer near the soil surface was positionally unavailable because there was no soil water for plant roots to obtain it

Where did high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen come from in fields that had decent crop yields?

In 2021, crop water use demanded a lot of stored soil water uptake from deeper in the soil profile. If the crop was able to root down deep enough and fast enough, the crop found additional water in the subsoil along with nitrate-nitrogen from previous years. With the extra water and nitrate found in the deep subsoil (below 24 inches), the resulting crop yield surprised many farmers and agronomists. Just because we do not routinely collect soil samples below the 24-inch soil depth in most areas does not mean there is zero nitrate-nitrogen down there. After a series of wet years, the amount of nitrate-nitrogen that can accumulate in the lower soil profile can be considerable. In a drought year, when all crops were forced to root deeper just to survive, the deep nitrate-nitrogen makes a significant contribution to the total plant nitrogen uptake.

What about the nitrogen fertilizer that was applied last spring and all the nitrate-nitrogen in the topsoil (0-6 inch soil profile)?

With the very dry topsoil conditions, plant roots grew deeper in search of water. Since plant roots obtain most nitrate-nitrogen through mass flow in soil water, this situation left fertilizer nitrogen “stranded” and positionally unavailable near the soil surface. Although this was bad for this year’s crop, the “stranded” nitrogen is in a good position for next year’s crop. We experienced the same phenomenon in 2017 and 2018, after some areas had experienced a severe drought. There were fields with decent crop yields and considerable “stranded” nitrogen, just like this year.

Strategies to utilize high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen for next year

With so many wheat fields with high residual soil nitrate-nitrogen this fall, you may want to consider changing your crop rotation. Severe droughts like 1988 and 2021 are not very common, so we need to think outside the box. It is common for wheat to be followed in the crop rotation with a legume like soybean or dry edible bean. However, the drought has left you with a lot of residual soil nitrate-nitrogen, and nitrogen fertilizer prices are staggeringly high right now. If you have 100 lb/acre nitrate-N (0-24 inch soil profile), that is $60 per acre of “free” nitrogen fertilizer at current urea prices ($550/ton). In addition, excess soil nitrate-nitrogen can also make soybean iron deficiency chlorosis (IDC) worse on moderate to high IDC risk soils. Do you want to sacrifice $60 per acre of “free” nitrogen AND risk lowering soybean yield due to more severe soybean IDC?

Drought can be sporadic or continue for multiple years. You may want to consider more short-season crops in the crop rotation that require less water and can produce well in drier years (remember, we used most of the stored soil water in 2021). Short-season crops to consider include winter wheat, spring wheat, durum wheat, barley, canola, etc. It is also important to consider the current price for each crop. With high crop prices right now and promising futures prices in 2022, you could lock in some good prices for next year. Although two consecutive years of the same crop (e.g. wheat) is not ideal for disease management, there was very little disease in 2021, and it might allow some different weed control options for future crops in the rotation. All in all, a drought brings opportunities to think outside the box.