Adjusting high soil pH and salinity with sugar beet-processing spent lime

The sugar beet processing industry uses large quantities of fine-ground, high-grade calcium carbonate (lime) to purify sucrose in the sugar extraction process. The by-product spent lime retains high reactivity and purity, making it an attractive liming material for acidic soils. Application of spent lime is a common practice through the sugar beet producing areas of the upper Midwest and northern Great Plains, where its primary function is the suppression of the soil-borne disease Aphanomyces root rot of sugar beet. The spent lime also contains about 20 lb P2O5 per ton, mostly as organic phosphorus impurities gained from sugar refining.

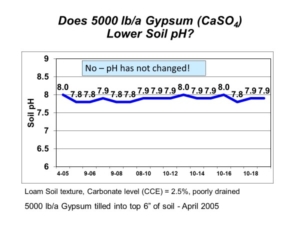

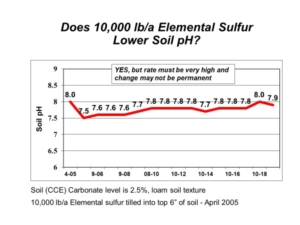

We often get questions about correcting high soil pH and salinity with spent lime. Salt-affected soils, saline and sodic, are a common problem across the northern Great Plains. These soils have high soil pH and present numerous agronomic and soil management problems. The soil amendment gypsum (calcium sulfate) is often applied to sodic soils (those with high sodium) to combat soil swelling and dispersion. The spent lime (calcium carbonate) also contains calcium, but it is very insoluble at high soil pH.

Each year, we get many questions about applying spent lime on soils with high pH and salinity. To answer these questions, AGVISE Laboratories installed a long-term demonstration project in 2008 to evaluate adjusting high soil pH and salinity with spent lime. We applied multiple spent lime rates and tracked soil test levels over seven years. There were no significant changes or trends in soil pH (Table 1) or salinity (Table 2). This is no surprise because the initial soil pH was high and buffered around 7.8-8.2, indicating the presence of natural calcium carbonate. If the soil already contains naturally occurring lime, what is the good of adding more lime? Moreover, calcium carbonate is very insoluble, so there is no expectation that more lime will decrease or increase salinity.

Since soil test levels did not change over seven years, we terminated the project in 2014. The research question was a conclusive dud. While spent lime is useful to amend acidic soils and suppress Aphanomyces root rot of sugar beet, it does not help on soils with high pH or salinity.

| Table 1. Soil pH (1:1) following sugar beet-processing spent lime application on high pH soil. | ||||||||

| Spent Lime | Year | Average | ||||||

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | ||

| ton/acre | ||||||||

| 1 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.80 |

| 2 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.94 |

| 3 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.95 |

| 4 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 8.0 | 7.85 |

| 5 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.90 |

| 6 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.00 |

| Spent lime applied and incorporated September 2008. Soil sampled in fall. | ||||||||

| Table 2. Soil salinity (electrical conductivity, EC 1:1) following sugar beet-processing spent lime application on moderately saline soil. | |||||||

| Spent Lime | Year | ||||||

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| ton/acre | ——————— dS/m ——————— | ||||||

| 1 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.8 |

| 2 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 4 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 5 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 6 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| Spent lime applied and incorporated September 2008. Soil sampled in fall. | |||||||