Starter Fertilizer: Choosing the Right Rate

Starter fertilizer placed with or near the seed is essential for vigorous early season growth in grass crops such as corn and wheat. We plant these crops early because we know vigorous early season growth is important to achieving high crop yields. Early planting also means cold soils, and starter fertilizer is necessary to get the crop going with a good start. Each spring, we receive many questions about starter fertilizer placement and seed-safe fertilizer rates. These questions come from farmers who want to plant as many acres per day as possible, take advantage of more efficient banded phosphorus placement, and of course reduce fertilizer costs.

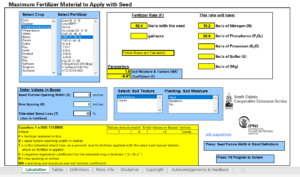

The two most common questions we get are “What is highest rate of starter fertilizer I can apply with the seed?” and “What is the lowest rate of starter fertilizer I can apply with the seed and still get a starter effect?” South Dakota State University (SDSU) made a downloadable spreadsheet that calculates the maximum seed-safe fertilizer rate (Figure 1). The spreadsheet will ask for the crop choice, fertilizer product, seed opener width, row spacing, tolerable stand loss, soil texture, and soil water content. The spreadsheet calculations are based on SDSU greenhouse and field studies.

Figure 1. Fertilizer Seed Decision Aid from South Dakota State University. Download the spreadsheet here.

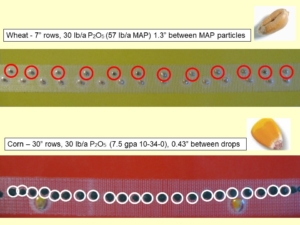

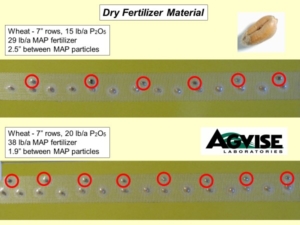

Research has shown, that to achieve the full starter effect, a fertilizer granule or droplet must be within 1.5 to 2.0 inches of each seed. If the fertilizer granule or droplet is more than 1.5 to 2.0 inches away from the seed, the starter effect is lost. To illustrate the role of starter fertilizer rates and seed placement, AGVISE put together displays showing the distance between fertilizer granules or droplets at various rates and row spacings. For example, take a look at wheat planted in 7-inch rows with 30 lb/acre P2O5 (57 lb/acre 11-52-0) and corn planted in 30-inch rows with 30 lb/acre P2O5 (7.5 gal/acre 10-34-0). You need to maintain a sufficient starter fertilizer rate to keep fertilizer granules or droplets with 1.5 to 2.0 inches of each seed.

Figure 2. Two examples from the AGVISE Starter Fertilizer Display series. Find more crops and fertilizer rates here.

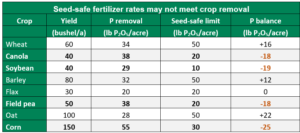

In the northern Great Plains and Canadian Prairies, most fertilizer is applied at planting and often as seed-placed fertilizer. This creates a challenge to prevent soil nutrient mining when balancing seed safety and crop nutrient removal with higher crop yield potential. Soil nutrient mining occurs when you apply less fertilizer than crop nutrient removal, resulting in soil test P and K decline over time. Some broadleaf crops, like canola and soybean, are very sensitive to seed-placed fertilizer, allowing only low seed-placed fertilizer rates. In contrast, most cereal crops can tolerate higher seed-placed fertilizer rates. To maintain soil nutrient levels across the crop rotation, you need to apply more phosphorus fertilizer in crops that allow greater seed safety. You can apply more phosphorus fertilizer with crops like corn or wheat, which allows you build soil test P in those years, while you mine soil test P in canola or soybean years. If you cannot the maintain crop nutrient removal balance with seed-placed fertilizer, then you need to consider applying additional phosphorus in mid-row bands or broadcast phosphorus at some point in the crop rotation.

Table 1. Seed-safe fertilizer rates may not meet crop removal. In the example, the seed-safe limit is based on 1-inch disk or knife opener and 7.5-inch row spacing for air-seeded crops and 30-inch row spacing for corn. Phosphorus (P) balance: Seed-safe limit (lb/acre P2O5) minus crop P removal (lb/acre P2O5). A negative P balance indicates the seed-safe limit does not meet crop removal, which may decrease soil test P.

Starter fertilizer is an important part of any crop nutrition plan. Here are more resources to help you make the best decisions on starter fertilizer materials, placement, and rates.

Fertilizer Application with Small Grain Seed at Planting, NDSU

Safe Rates of Fertilizer Applied with the Seed, Saskatchewan Agriculture

Using banded fertilizer for corn production, University of Minnesota

Corn response to phosphorus starter fertilizer in North Dakota, NDSU

Wheat, barley and canola response to phosphate fertilizer, Alberta Agriculture