5 Things You Should Know About Calcium

1. Calcium (Ca) is abundant in soils of the upper Midwest, northern Great Plains, and Canadian Prairies; calcium deficiency in agronomic crops is rare

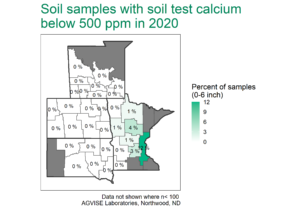

Calcium makes up about 3.6% of the Earth’s crust, and it is relatively abundant in agricultural soils across the region. In soils with pH greater than 6.0, Ca is the dominant cation (positively charged ion) on the cation exchange capacity (CEC). Since most soils in the region have a pH of 6.0 or above, calcium is very abundant and soils with low soil test Ca (less than 500 ppm) are rare (Figure 1).

Figure 1. AGVISE regional soil test summary. AGVISE has created regional summaries for the past 40 years. You can find more soil test summary data, including Montana and Canada, here.

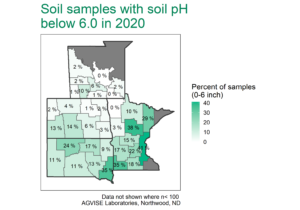

Potential calcium deficiencies are most common on sandy soils with strongly acidic pH (pH less than 5.0). Luckily, the fix for low soil pH also fixes potential Ca deficiencies. To correct soil pH, agricultural limestone is applied to raise soil pH to 6.0 or 6.5, if growing sensitive crops like alfalfa or clover. When limestone (calcium carbonate) is applied in tons per acre, more than enough calcium is also applied and sufficiently increases soil test Ca, providing ample calcium for optimal crop growth and development. Throughout the region, soils with low soil pH are more common in the higher rainfall areas to the east and south (Figure 2), and liming is a standard practice to correct soil pH and provide calcium.

Figure 2. Soil samples with pH below 6.0 in 2020, where lime application may be required. The number of fields with low pH has increased over time and will continue to do so because soil acidification is a natural process. Keep watch for low soil pH, especially in western North Dakota and South Dakota. You can find more soil test summary data, including Montana and Canada, here.

2. Multiple calcium fertilizer sources exist; some increase pH, others do not

Agricultural limestone is the most common lime source and is available in two flavors: calcitic (calcium carbonate, <5% magnesium) or dolomitic (calcium-magnesium carbonate, >5% magnesium). Limestone quarries exist in southern Minnesota and Iowa, but the northern Great Plains is virtually devoid of mineable limestone. Industrial waste lime (spent lime) is another good lime source and available from sugar beet processing plants and water treatment plants throughout the region. Any of these liming materials will supply enough calcium to increase soil test Ca if soil pH is increased above pH 6.0.

Gypsum (calcium sulfate) is another calcium source, but it does not change soil pH. Gypsum is sometimes used to increase soil test Ca if the producer does not want to increase soil pH with lime application. This situation is common in irrigated potato production where increased soil pH may increase soil-borne diseases like common scab of potato. Gypsum is not a lime source, so it will not increase soil pH.

3. There is no “ideal” base cation saturation range or ratio for calcium

Suggestions that Ca and other base cations (magnesium, potassium) are required in a certain percentage or ratio in soil are not supported by modern science. Recent research done at several universities shows a wide range of base cation ratios in soil will support normal crop growth (see links below). What is important is that a sufficient soil test amount of each base cation (Ca Mg, K) is present in soil to support plant growth and development.

4. Soils with pH greater than 7.3 will have falsely inflated soil test Ca and cation exchange capacity (CEC) results

Soils with pH greater than 7.3 will contain some amount of naturally occurring calcium carbonate (CaCO3), shown on the soil test report as carbonate (CCE). The calcium soil test method will extract Ca on cation exchange sites and some Ca from calcium carbonate minerals, resulting in an inflated soil test Ca result. Starting with inflated soil test Ca, the routine cation exchange capacity (CEC) calculation is also inflated. For example, a soil with pH 7.8 and 3.0% CCE may report CEC at 60 meq/100 g, but the correct CEC is only 27 meq/100 g. To obtain accurate CEC results on soil with pH greater than 7.3, a special displacement CEC laboratory method is required. For soils with pH less than 7.3, the routine CEC calculation method will provide accurate soil test Ca and CEC results. High soil salinity (soluble salts, EC) can also inflate CEC results.

5. Calcium is not an environmental risk to surface or ground water

Calcium is one of the major dissolved substances found in surface and ground waters, especially in the northern Great Plains and Canadian Prairies. In fact, water hardness is determined from the amount of dissolved calcium and magnesium in water. There is already so much calcium found in natural waters in the region that calcium fertilizer additions to soil are negligible. Water hardness does affect the effectiveness of some herbicides and may cause tank-mixing issues, but is not an environmental concern.

Bonus: Just because your tomatoes have had blossom-end rot does NOT mean your soil is Ca deficient!

If you are a backyard tomato grower, you may have experienced blossom-end rot before, where the blossom-end of developing fruits turn brown and mushy while still on the plant. Yes, the problem is caused by low calcium in the tomato plant, but not necessarily because the soil has low soil test Ca. Blossom-end rot is primarily caused by inconsistent soil moisture. Adequate soil moisture is required to maintain a consistent supply of calcium moving to the plant root, which might run short if watering is inconsistent. To keep blossom-end rot away from your garden, just try to be more consistent with watering, especially during dry periods.

Resources on Base Cation Saturation Ratios

Cation Exchange: A Review, IPNI

Soil Cation Ratios for Crop Production, UMN

A Review of the Use of the Basic Cation Saturation Ratio and the “Ideal” Soil, SSSA Journal