In 2020, there are again widespread acres of Prevented Planting (PP) in North Dakota and northwest Minnesota. Farmers are now making plans to plant cover crops on unplanted cropland in the next few weeks. It is important to establish cover crops on PP fields because growing plants help reduce the chance these fields will be PP fields again next year.

Let’s look at the major reasons why cover crops are valuable tools on Prevented Planting acres.

Soil Water Use

A field without any growing plants is a fallow field. Before no-till, summer fallow was a widespread soil water conservation strategy in dryland agriculture. Actively growing plants transpire (use) a lot more water than evaporation from the soil surface alone does. Cover crops help fill the water-use void by transpiring a lot of water, helping to dry the soil surface and lower the water table before the following year. This also opens space in the soil profile for summer and fall rains to leach soluble salts from the soil surface and reduce salinity in the root zone.

Soil Erosion Control

Tillage is a popular weed control tool, but it also destroys crop residue and leaves soil exposed and vulnerable to water and wind erosion. Planting cover crops protects the soil surface from rain and wind, keeping soil firmly in place. Just because you cannot grow a cash crop on the field this year, you should not let your soil blow into the next field, letting your neighbor farm it next year.

Weed Control

An established cover crop can compete with weeds, helping suppress weed growth and weed seed production. For fields with problematic broadleaf weed histories, a cover crop mix containing only grass species is preferred. In grass cover crops, you can still use selective broadleaf weed herbicides to control the problematic broadleaf weeds of conventional or no-till systems such as Canada thistle, common ragweed, kochia, volunteer canola, and waterhemp while not killing the grass cover crop. For fields with low weed pressure, a cover crop mix containing grasses, brassicas, and legumes will provide more soil health benefits.

Soil Biological Activity

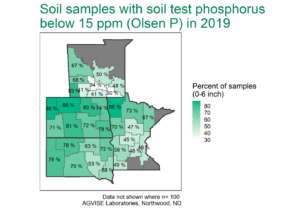

Have you heard about “fallow syndrome” before? Fallow syndrome is an induced nutrient deficiency, often seen in corn following fallow, when the population of mycorrhiza fungi is insufficient to colonize plant roots and help them acquire water and nutrients. Mycorrhizae are especially important in plant uptake of phosphorus, so plants with fallow syndrome often show phosphorus deficiency symptoms. Fallow syndrome is a major concern in corn following summer fallow or Prevented Planting without cover crop.

During the Prevented Planting year, it is important to include grass species in the cover crop mix to support and maintain the mycorrhiza population through next year. Brassica species, like radish and turnip, are often included in cover crop mixes for their deep taproot architecture and high forage value for grazing livestock, but brassicas do not support mycorrhizae. You do not want a cover crop mix consisting of brassica species alone because fallow syndrome might occur next year.

In June 2020, excessive rainfall slammed some parts of the upper Midwest and northern Great Plains, drenching soils with 3 to 15 inches of rain over a couple days. On summer-flooded fields, cereal rye is an attractive soil management tool. You can plant or fly on cereal rye well into August or mid-September, and it will continue to use soil water through late summer and fall. Next spring, the overwintered rye will grow again, using more soil water and maintaining soil structure, providing you with a much better chance to plant the field. If soybean is the next crop, you can plant glyphosate-tolerant soybean into green cereal rye then terminate the cereal rye with glyphosate later. This practice has become more and more popular on difficult fields.

In June 2020, excessive rainfall slammed some parts of the upper Midwest and northern Great Plains, drenching soils with 3 to 15 inches of rain over a couple days. On summer-flooded fields, cereal rye is an attractive soil management tool. You can plant or fly on cereal rye well into August or mid-September, and it will continue to use soil water through late summer and fall. Next spring, the overwintered rye will grow again, using more soil water and maintaining soil structure, providing you with a much better chance to plant the field. If soybean is the next crop, you can plant glyphosate-tolerant soybean into green cereal rye then terminate the cereal rye with glyphosate later. This practice has become more and more popular on difficult fields.

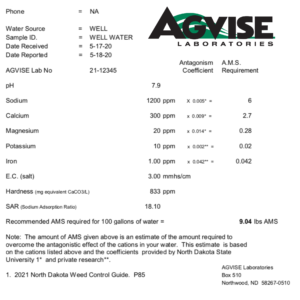

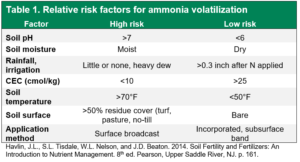

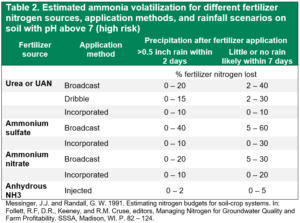

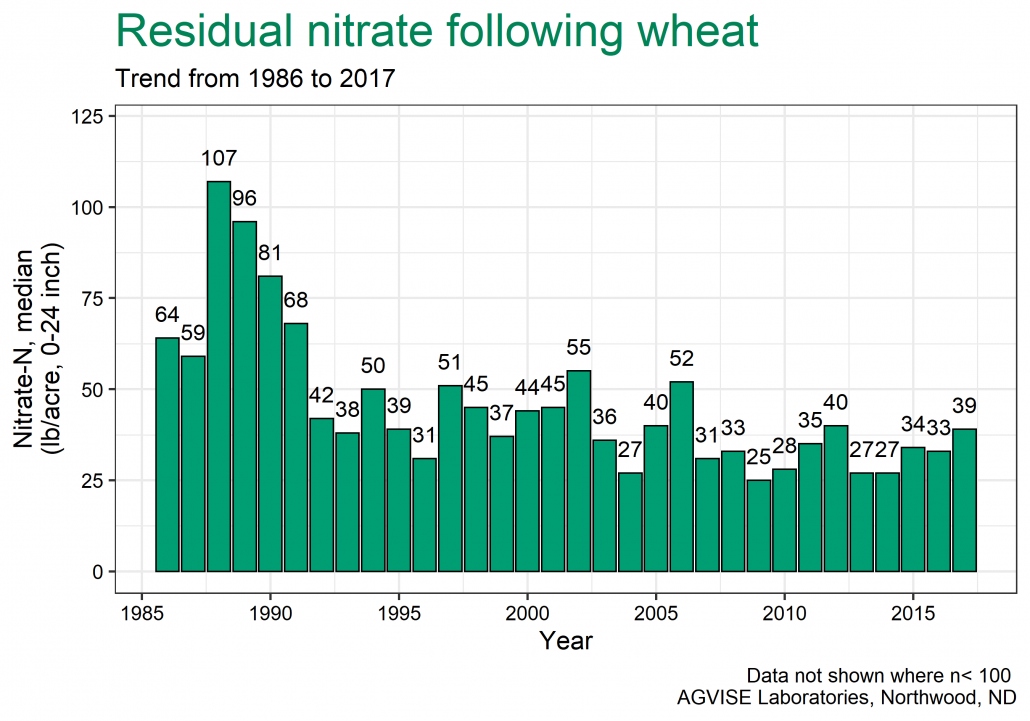

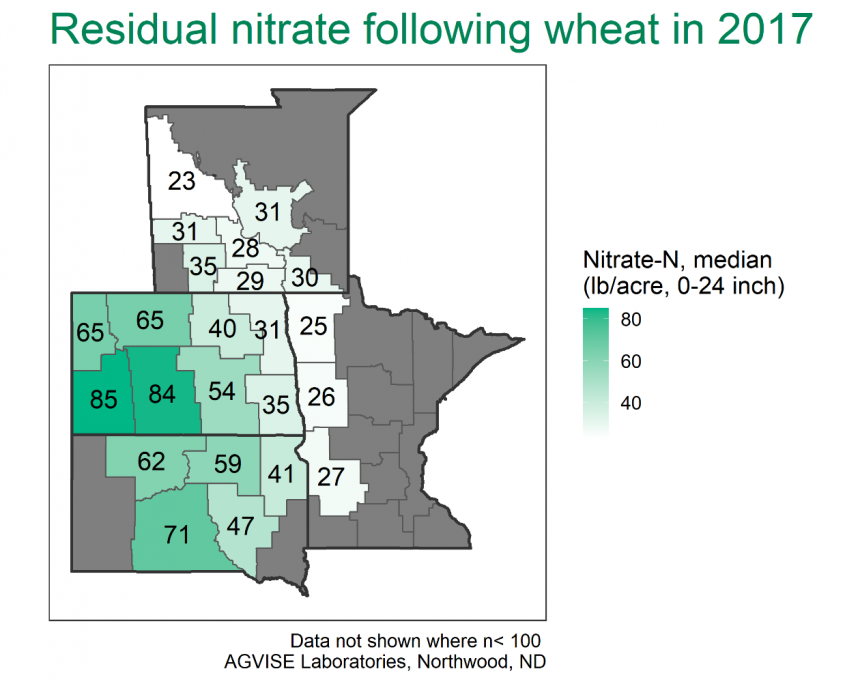

Do not forget about soil fertility and plant nutrition for cover crops. A modest application of nitrogen will help cover crop establishment, plant water use, and competition with weeds, as cover crops with adequate nitrogen will grow faster and larger than those without nitrogen. Around 46 lb/acre nitrogen (100 lb/acre urea, 46-0-0) should be enough to establish nice cover crop growth. Prevented Planting fields, being wetter than those successfully planted in spring, lost some, if not most, soil nitrogen via nitrate leaching or denitrification. Although additional nitrogen may have mineralized from soil organic matter during May and June, excess precipitation in June may have caused additional soil nitrogen loss. The best way to know is collecting 0-12 or 0-24 inch soil samples for nitrate-nitrogen analysis.

As you choose the appropriate cover crop mix on Prevented Planting fields, you must consider the pros and cons of each cover crop species and how each will help accomplish your goals. These are some helpful resources that will provide additional information on what cover crop options will work best on your fields.