Sodic Soil Problems? Try the NDSU Gypsum Requirement Calculator

This article originally appeared in the AGVISE Laboratories Spring 2025 Newsletter.

Salinity and sodicity are two related but distinct terms to describe salt-affected soils. Salinity is the overall abundance of soluble salts, which compete with plant water uptake and reduce crop productivity. Salinity is measured as soluble salts (mmhos/cm or dS/m) on soil test reports. Sodicity specifically refers to high sodium in soil that destroys soil structure, resulting in poor water movement, poor trafficability, and soil compaction. Sodicity is measured as extractable sodium percentage (%Na) or sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) on soil test reports.

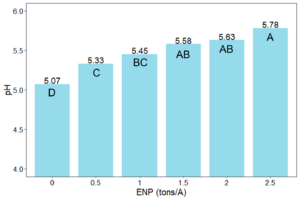

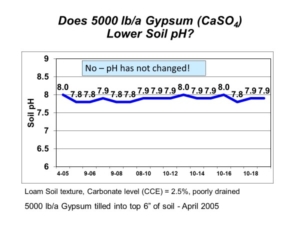

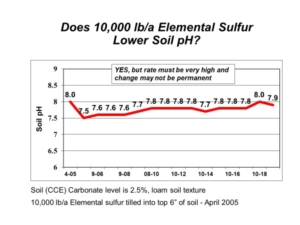

Saline soils have an overall abundance of soluble salts, which must be managed with salt-tolerant plant species or improved soil water management (tile drainage). There is nothing you can add to make the salts disappear, such as the mistaken suggestion to apply gypsum to saline soils. Gypsum, however, can be an effective amendment for sodic soils (those with low salinity yet high sodium). A soluble calcium source, like gypsum, can help reduce soil swelling and dispersion and help improve soil structure and water movement on troublesome sodic soils.

The amount of gypsum required is often in tons per acre. This is no task accomplished with a few hundred pounds of gypsum. To calculate the amount of gypsum needed, North Dakota State University has released a gypsum requirement calculator, available online: https://www.ndsu.edu/pubweb/soils/GypsumRequirementWebApp/ The calculator will ask for the soil depth to amend, soil bulk density, CEC, gypsum purity, and initial/target SAR values.