5 Things You Should Know About Phosphorus

1. The two accepted soil phosphorus tests in the North Central Region are the Olsen and Bray-P1 methods

The Olsen (bicarbonate) method is the standard soil P test in the North Central region. This method was developed to work on soils with low and high pH. The Olsen method works well in precision soil sampling, where the same field may have zones with acidic and calcareous soils. The Bray P-1 method is another accepted method in our region, but not always recommended. This method was developed in the U.S. Corn Belt, has a long history of soil test calibration studies and works well on acidic soils. The Bray P-1 method fails on soils with pH greater than 7, producing results with false low soil test P. Therefore, it has remained limited to the U.S. Corn Belt proper. The Mehlich-3 method was introduced as a multi-nutrient soil extractant. But like the Bray P-1 method, the acidic Mehlich-3 method does not perform well on calcareous soils; therefore, it has not gained approval by universities in the northern Great Plains and Canadian Prairies.

All soil P test methods are designed to predict the probability of crop response to P fertilization. The methods measure the plant-available P pool. Since the soil test method is an index of availability, the units are reported in parts per million (ppm) and ranked low, medium, or high based on university soil test calibration research. No soil P test method measures the actual pounds of available P in soil, they are only indexes of crop response.

2. Most soils in the Northern Plains/Canadian Prairies region could use more phosphorus

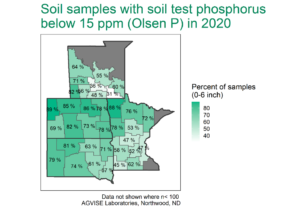

Soils in the region are naturally low in P and historical P fertilizer use has been low, relative to crop P removal. As a result, many areas in the region still have low soil test P (below soil test critical level of 15 ppm Olsen P) after many decades of crop production. In other words, most farmers are not over-applying P. In fact, soils with low soil test P should receive moderate to high rates of fertilizer P each year to achieve good crop yield and maximize profitability.

Figure 1. Map developed using AGVISE soil test data. AGVISE has created regional summaries like this for the past 40 years. Check out the summary data for Montana and Canada and summaries of other nutrients and soil properties here.

3. You should use starter phosphorus fertilizer

Starter fertilizer placed near, or with the seed, is critical for crops like corn and wheat, regardless of soil test P level. A P fertilizer band placed near the seed will ensure soluble P near developing plant roots and results in vigorous early season growth, which is important in cold, wet soil conditions. Placing P fertilizer in bands also improves P use efficiency, especially in soils with relatively low or high pH. Phosphorus availability is greatest near soil pH 6.5. Since changing soil pH is difficult and costly, fertilizer P use efficiency is more easily improved with application in fertilizer bands to reduce the volume of soil involved in P fixation reactions.

4. Phosphorus source doesn’t really matter

No matter the starting material, all P fertilizers go through the same chemical reactions in the soil. It does not matter if the fertilizer starts as a poly-phosphate or ortho-phosphate. Within about one week in the soil, all P fertilizer sources react to form lower solubility compounds. What is more important than source is the placement of the fertilizer to increase availability (banding) and the rate of actual P fertilizer applied.

5. Phosphorus can be an environmental concern

Phosphorus entering surface waters can create algae blooms and fish kills. Since P is not mobile in soil, the P leaching risk is very low. However, P does move to surface waters with soil particles when erosion occurs. In cold climates like those on the northern Great Plains and Canadian Prairies, dissolved P released from vegetation can move with snow melt to surface water.

For more information about phosphorus and its reactions in soil, explore the links below:

Understanding Phosphorus in Minnesota Soils (Univ. Minnesota)

Understanding Plant Nutrients: Soil and Applied Phosphorus (Univ. Wisconsin)

Phosphorus Facts: Soil, plant, and fertilizer (Kansas State Univ.)