Fertilizing soybean

Soybean acres expanded greatly across the northern Great Plains and into Manitoba through the 1990s and 2000s. Today, soybean occupies a large portion of planted acres and makes a desirable rotation crop in canola, corn, and small grain production systems. As soybean has advanced northward and westward, soybean is often billed as a low maintenance crop, requiring no fertilizer or even seed inoculation. The fact is, if you expect soybean to be a low maintenance crop, you can expect low yield results. Achieving high soybean yields starts with a good, long-term soil fertility plan.

Nitrogen

Soybean yielding 40 bu/acre requires about 200 lb/acre nitrogen, but luckily you do not have to provide all the nitrogen! Soybean relies on nitrogen-fixing bacteria to meet its nitrogen requirements. Legumes, like soybean, form a symbiotic relationship with N-fixing bacteria, housed in root nodules, to provide sufficient nitrogen. Each legume species requires a unique N-fixing bacterium, thus an inoculant for lentil or pea does not work on soybean. Soybean seed must be inoculated with the N-fixing bacteria Bradyrhizobia japonicum. Ensure you have the proper soybean-specific seed inoculant. You can count the number of nodules on soybean roots and verify the presence of active N-fixing bacteria in the nodules with bright pink centers. These soybean plants have enough active N-fixing bacteria to meet soybean nitrogen requirements.

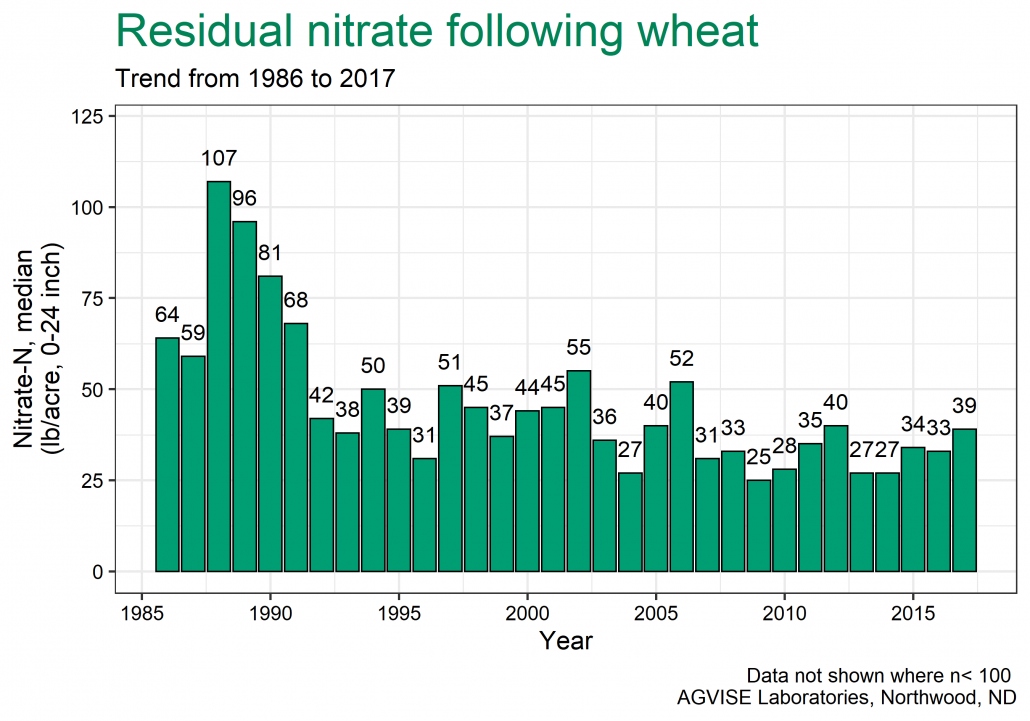

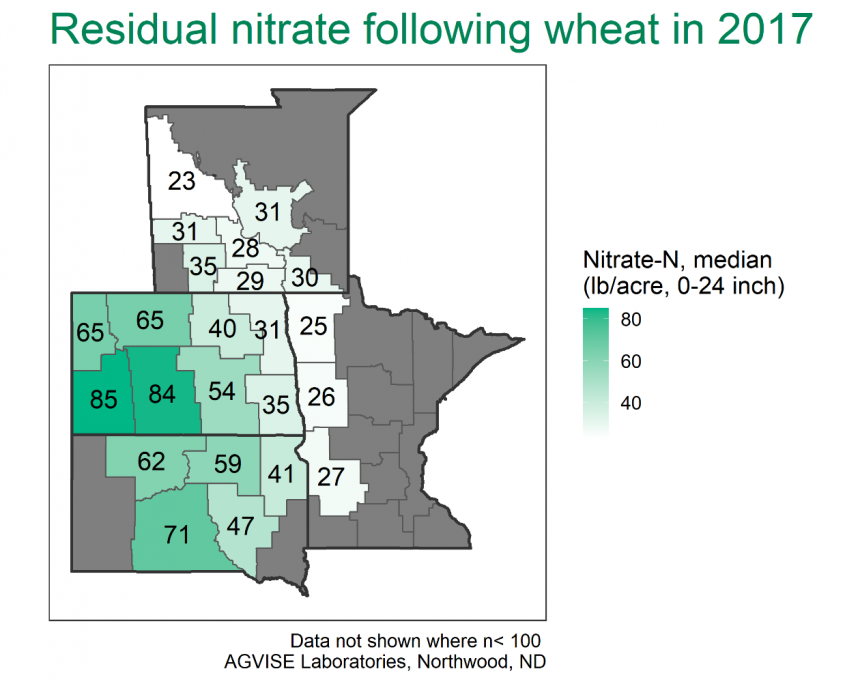

For new soybean growers, the N-fixing bacteria Bradyrhizobia japonicum is not naturally present in soil and seed inoculation is required. During the first few years of soybean establishment, supplemental nitrogen may be required to achieve good soybean yield while the N-fixing bacteria population builds. University of Minnesota researchers in the northern Red River Valley showed that soils with less than 75 lb/acre nitrate-N (0-24 inch) required 40-50 lb/acre additional preplant nitrogen. If successful inoculation and good nodule counts are observed in the first year, then no additional nitrogen should be required in subsequent years.

Plant soybean on soils with less than 100 lb/acre nitrate-N (0-24 inch), if possible. High residual soil nitrate may delay root nodulation with N-fixing bacteria and increase the severity of iron deficiency chlorosis (IDC). Because soybean can fix its own nitrogen, you may recoup better economic return on soils with high residual nitrate with crops that do not fix their own nitrogen like corn or wheat.

Phosphorus

Soybean does not respond to phosphorus as dramatically as grass crops like corn or wheat do. Nevertheless, medium to high soil test P are required to achieve good soybean yields. Soybean responds to broadcast P placement better than seed-placed or sideband P. In dryland regions where soybean is planted with air drills, seed-placed P or sideband P is often the only opportunity to apply phosphorus. You must pay special attention to seed-placed fertilizer safety with soybean. An air drill with narrow row spacing (6 inch) should not exceed 20 lb/acre P2O5 (40 lb/acre monoammonium phosphate, MAP, 11-52-0). Fertilizer rates exceeding the seed safety limit may delay seedling emergence and reduce plant population. For wider row spacings, no fertilizer should be placed with seed.

Potassium

Soybean removes far more potassium in harvested seed than canola or wheat. Soybean yielding 40 bu/acre removes about 60 lb/acre K2O, while wheat yielding 60 bu/acre removes only 20 lb/acre K2O. Pay close attention to potassium removal across the crop rotation. After soybean is added to the crop rotation, cumulative potassium removal greatly increases, and declining soil test K is observed over time.

Do not place potassium with soybean seed; delayed seedling emergence and reduced plant population can occur. Any potassium fertilizer should be broadcasted or banded away from seed.

Sulfur

Sulfur deficiency in soybean is uncommon, yet sometimes observed on coarse-textured soils with low organic matter (< 3.0%). Soybean response to sulfur is usually confined to certain zones within fields. With additional sulfur, soybean can produce more vegetative growth, but more vegetative growth may increase soybean disease severity, such as white mold. The residual sulfur remaining after sulfur-fertilized canola, corn, or small grain is often sufficient to meet soybean sulfur requirements.

Iron

Soybean is very susceptible to iron deficiency chlorosis (IDC). Soybean IDC is not caused by low soil iron but instead by soil conditions that decrease iron uptake by soybean roots. Soybean IDC risk and severity are primarily related to soil carbonate content (calcium carbonate equivalent, CCE) and worsened by salinity (electrical conductivity, EC).

Soybean IDC is common in the upper Midwest, northern Great Plains, and Canadian Prairies, where soils frequently have high carbonate and/or salinity. Within a field, IDC symptoms are usually confined to soybean IDC hotspots with high carbonate and salinity; however, symptoms may appear across a field if high carbonate and salinity are present throughout the field. Soybean IDC severity is made worse in cool, wet soils and soils with high residual nitrate. Soil pH is not a good indicator of soybean IDC risk because some high pH soils lack high carbonate and salinity, which are the two principal risk factors.

Guidelines for managing soybean IDC:

- Soil test each field, zone, or grid for soil carbonate and salinity. This may require soil sampling prior to soybean (possibly outside of your usual soil sampling rotation) or consulting previous soil sampling records.

- Plant soybean in fields with low carbonate and salinity (principal soybean IDC risk factors).

- Choose an IDC tolerant soybean variety on fields with moderate to high carbonate and salinity. This is your most practical option to reduce soybean IDC risk. Consult seed dealers, university soybean IDC ratings, and neighbor experiences when searching for IDC tolerant soybean varieties.

- Plant soybean in wider rows. Soybean IDC tends to be less severe in wide-row spacings (more plants per row, plants are closer together) than narrow-row spacings or solid-seeded spacings.

- Apply chelated iron fertilizer (e.g., high quality FeEDDHA) in-furrow at planting. In-furrow FeEDDHA application may not be enough to help an IDC susceptible variety in high IDC risk soils (see points #2 and #3).

- Avoid planting soybean on soils with very high IDC risk.

Zinc

Zinc deficiency in soybean is rare, even on soils with low soil test Zn. Soybean seed yield response to zinc is limited on soils with less than 0.5 ppm Zn. More zinc sensitive crops like corn, dry bean, flax, and potato will respond to zinc on soils with less than 1.0 ppm Zn. If zinc sensitive crops also exist in the crop rotation, you may apply zinc with broadcast phosphorus or potassium during the soybean year as another opportunity to build soil test Zn across the crop rotation.